Home / Disorders of Aggression

DISORDERS OF AGGRESSION

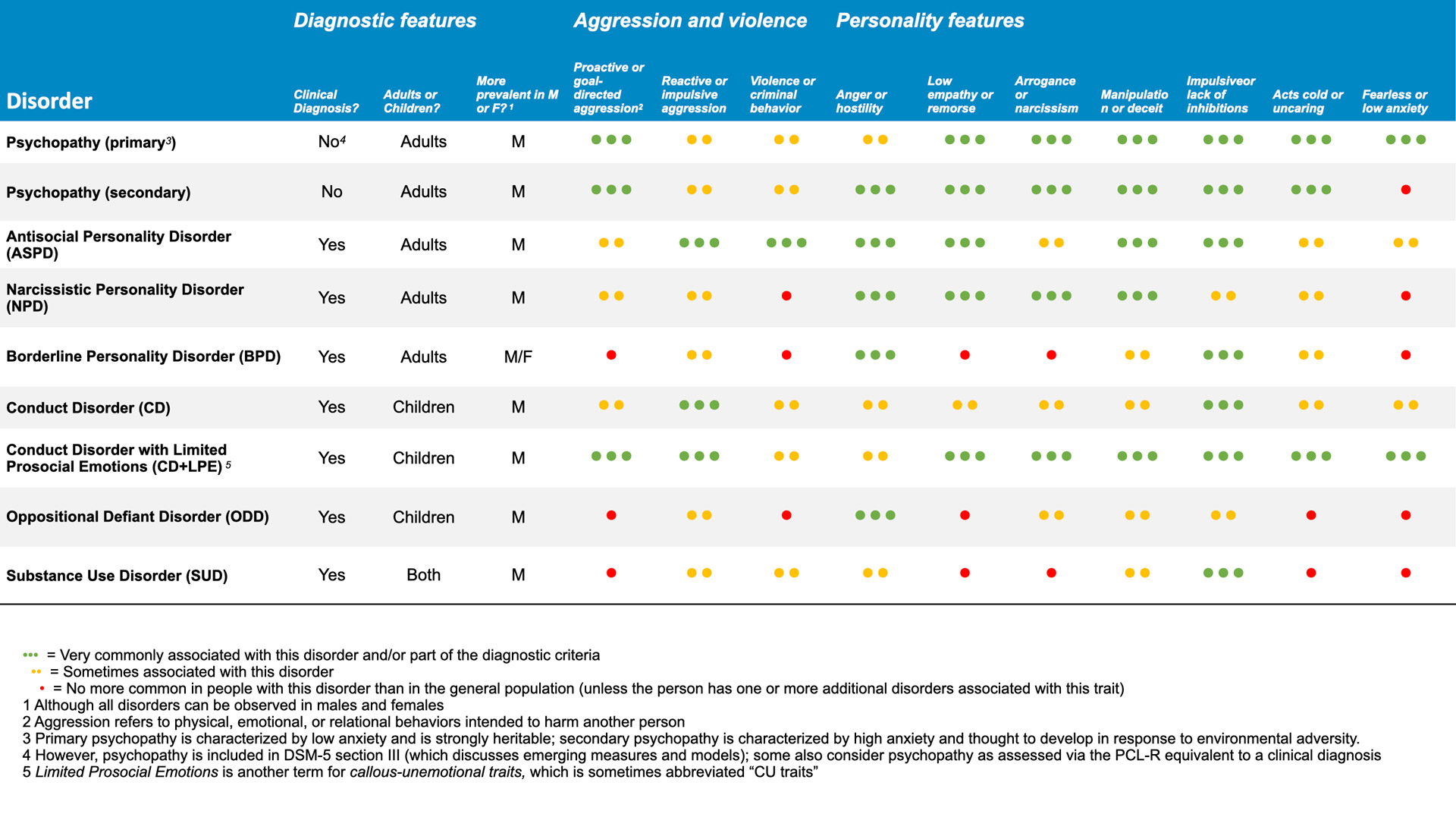

Disorders of aggression are psychological disorders that typically are associated with aggression, or that include aggressive behavior among the criteria for diagnosis. “Aggression” refers to any behavior intended to cause harm to another individual. It includes physical aggression (such as hitting or kicking), emotional aggression (such as making threats), and social aggression (such as bullying).

Are disorders of aggression “real” disorders?

Disorders of aggression qualify as psychological disorders according to the The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), which are the manuals used by psychologists, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals to classify disorders and make diagnoses. A psychological disorder is defined as a persistent pattern of behavior, thoughts, and feelings that:

- Are not typical (in other words, are different from what the majority of people experience)

- Are associated with differences in brain structure and function

- Cause difficulties functioning in social relationships, work, and other life domains.

All disorders of aggression, including Conduct Disorder (CD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD), Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), and psychopathy meet these criteria. It is important to remember that people don’t choose to have these disorders, just like people don’t choose to have schizophrenia, depression, or anxiety. It is also important to remember that like other disorders, disorders of aggression are treatable.

With the exception of psychopathy, more information about these disorders can be found in The DSM-5 or the ICD-10. More information about psychopathy can be found on the website Psychopathy Is.

What sets disorders of aggression apart from other disorders?

Many familiar psychological disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are characterized by “internalizing,” or negative feelings and behaviors that are internal or directed toward the self. People with internalizing disorders may feel intense worry, sadness, self-blame or guilt. They may feel worthless, or may harm themselves.

By contrast, disorders of aggression are “externalizing” disorders. This means they are characterized by negative behaviors and feelings that are directed toward other people. People with externalizing disorders may show anger, frustration, defiance, or aggression directed at other people. Many people with disorders of aggression have multiple diagnoses, including depression or anxiety, and so may have both internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

What are the specific disorders of aggression?

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD)

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD). ODD is characterized by frequent irritability, argumentativeness, and defiant and/or spiteful behavior. Children with ODD may be both socially and verbally aggressive and may do things to annoy or provoke others on purpose. Physical aggression is not one of the diagnostic criteria for ODD. ODD is often considered a developmental precursor to Conduct Disorder (CD). This means a child with ODD is at much higher risk for developing CD.

- ODD most commonly emerges in children around 6 to 8 years old, but can begin earlier or later.

- Up to 16% of children have symptoms that would qualify them for a diagnosis of ODD.

- Worried about a child you know? Take our ODD screener.

Description of a child who would qualify for a diagnosis of ODD

“Ben” is an 8-year-old boy. He has had difficulties controlling his behavior since he was a young child. He is often irritable, and his parents feel they are “walking on eggshells” to avoid upsetting him. He loses his temper frequently when asked to do things by adults, such as putting away his toys or setting the table for dinner. He will refuse to comply, and may scream or throw things. In school, he is often asked to sit apart from other students, as he verbally provokes others who are sitting nearby him. When singled out, he argues and tries to blame other children.

Conduct Disorder (CD)

Conduct Disorder (CD). CD is characterized by frequent destructiveness, deceit, rule-breaking, and aggression, including verbal, social, and physical aggression. CD places a child at high risk for developing adult disorders of aggression in the future, such as Antisocial Personality Disorder or psychopathy.

- Childhood-onset CD emerges before the age of 11. Children with childhood-onset CD tend to have more neural and cognitive impairments and a more serious prognosis than children with CD that emerges later.

- Adolescent-onset CD emerges in children 12 or older. It often is seen in adolescents who befriend other teens with delinquent behavior.

- Up to 10% of children have symptoms that would qualify them for a diagnosis of CD.

- Worried about a child you know? Take our CD screener.

Description of a child who would qualify for a diagnosis of CD

Conduct Disorder with Limited Prosocial Emotions (CD+LPE)

Conduct Disorder with Limited Prosocial Emotions (CD+LPE). CD+LPE is characterized by frequent destructiveness, deceit, rule-breaking, and aggression, in addition to low empathy and remorse, an uncaring nature, and shallow displays of emotions such as fear, sadness, or love. These features are called “Limited Prosocial Emotions” in the DSM-5. They are also known as callous-unemotional traits or CU traits. Children with these traits are at very high risk for developing psychopathy in adulthood.

- CD+LPE typically emerges around the age of 12, although symptoms can appear earlier or later, and it has a more serious prognosis than CD without LPE.

- Up to 3% of children have symptoms that would qualify them for a diagnosis of CD+LPE.

- Worried about a child you know? Take our conduct disorder and callous unemotional traits screeners.

Description of a child who would qualify for a diagnosis of CD+LPE

“Ashley” is a 10 year old girl. She has been having problems at school and at home off and on for roughly four years. She appears cold and resists affection from her parents and brother. Although she can be friendly and charming, she has trouble keeping friends. She has been caught stealing from other children and has threatened to hurt them if they tell on her. When caught misbehaving, she does not appear to feel any guilt or remorse. She is unusually fearless. She does not seem concerned about being punished for her behavior, or about getting hurt when she does risky things.

Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED)

Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED). IED is characterized by frequent (at least twice per week) sudden, uncontrolled outbursts of anger or aggression. People with this disorder may assault others, destroy property, or start fights during an outburst. The outbursts are not planned, are not committed to achieve a goal, are out of proportion to the incident that provoked them, and are usually brief. Typically, these outbursts cause the person significant distress afterward. IED can be diagnosed in both children and adults.

- IED most commonly emerges around age 12, but it can appear earlier or later.

- Up to 8% of children and up to 7% of adults have symptoms that would qualify them for a diagnosis of IED.

Description of a child who would qualify for a diagnosis of IED

The following disorders of aggression can be diagnosed only in adults ages 18 and older:

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD)

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD). ASPD is characterized by frequent aggression, criminal behavior, deceit, rule-breaking, impulsiveness, and/or lack of remorse. Although it is sometimes confused with psychopathy, only a minority of those who qualify for ASPD also have psychopathy.

- Up to 5% of adults have symptoms that would qualify them for a diagnosis of ASPD

- Worried about yourself or someone you know? Take our ASPD screener.

Description of an adult who would qualify for a diagnosis of ASPD

Psychopathy (primary)

Psychopathy (primary). Psychopathy is characterized by a combination of personality traits that include callousness, boldness, social dominance, and impulsiveness or disinhibition. Psychopathy is a clinical disorder, even though it is not included by that name in the DSM-5 or the ICD-10. There are two forms of psychopathy: Primary and secondary psychopathy. Primary psychopathy is thought to be strongly related to genetic risk factors. People with primary psychopathy generally show stable levels of psychopathy over long periods of time. They have low levels of anxiety and fear, and may not have histories of severe trauma, abuse, or neglect that can explain their personality and behavior.

- Psychopathic traits vary continuously in the population. It is estimated that 1-2% of people have clinically significant levels of psychopathy.

- Worried about yourself or someone you know? Take our psychopathy screener.

Description of an adult who would qualify for a diagnosis of Psychopathy

“Ben” is a 30-year-old man. He works in sales where he is fairly successful. In conversation, he is charming, confident, and funny. However, he often struggles to keep a job. Often he claims he has quit or been laid off due to disagreements with co-workers or a boss. He denies that his behavior has played a role in his employment difficulties, although he acknowledges he is sometimes late or comes to work under the influence. He also acknowledges having embezzled from employers, but claims that’s in the past. In his personal life, he has had a series of short-term romantic relationships but says he has never been in love. Several relationships ended after a partner caught him cheating on them. He has had multiple tickets for speeding, running stoplights, and driving while impaired. He rarely expresses worries about the future or any other part of his life, but is content to drift between relationships and jobs.

Psychopathy (secondary)

Psychopathy (secondary). Secondary psychopathy is thought to result mostly from environmental factors. People with secondary psychopathy may show more changes in their personality and behavior over time (getting either worse or better). They tend to have high levels of anxiety and fear, and often have histories of severe trauma, abuse, or neglect.

- Psychopathic traits vary continuously in the population. It is estimated that 1-2% of people have clinically significant levels of psychopathy.

- Worried about yourself or someone you know? Take our psychopathy screener.

Description of an adult who would qualify for a diagnosis of secondary psychopathy

“Sam” is a 27-year-old woman. She is currently unemployed after having been arrested and imprisoned for domestic violence. She herself was abused and neglected by her mother and her mother’s boyfriends as a child. She loses her temper easily and admits that she is frequently violent toward romantic partners when they upset her. Often she uses charm or manipulation to prevent her romantic partners from leaving her after a fight, in part because she is often financially dependent on her partners. She can be very impulsive, making decisions to quit a job, leave school, or move to a new apartment without spending much time thinking about or planning for the consequences of doing so. She has significant debts and unpaid loans, in part due to her impulsive decisions related to both earning and spending money. She has used alcohol and drugs since she was a young teenager, and has been pulled over and jailed multiple times for driving under the influence.

Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED)

Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED). IED is characterized by frequent (at least twice per week) sudden, uncontrolled outbursts of anger or aggression. People with this disorder may assault others, destroy property, or start fights during an outburst. The outbursts are not planned, are not committed to achieve a goal, are out of proportion to the incident that provoked them, and are usually brief. Typically, these outbursts cause the person significant distress afterward. IED can be diagnosed in both children and adults.

- IED most commonly emerges around age 12, but it can appear earlier or later.

- Up to 8% of children and up to 7% of adults have symptoms that would qualify them for a diagnosis of IED.

More Information about Related Disorders

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). ADHD is characterized by frequent inattention (trouble staying focused), hyperactivity (excess movement) and impulsivity. ADHD is relatively common, and most people with ADHD are not antisocial. However, ADHD is closely linked to an increased risk for antisociality over the lifespan. And a majority of people with psychopathy or related disorders of aggression also meet criteria for ADHD.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

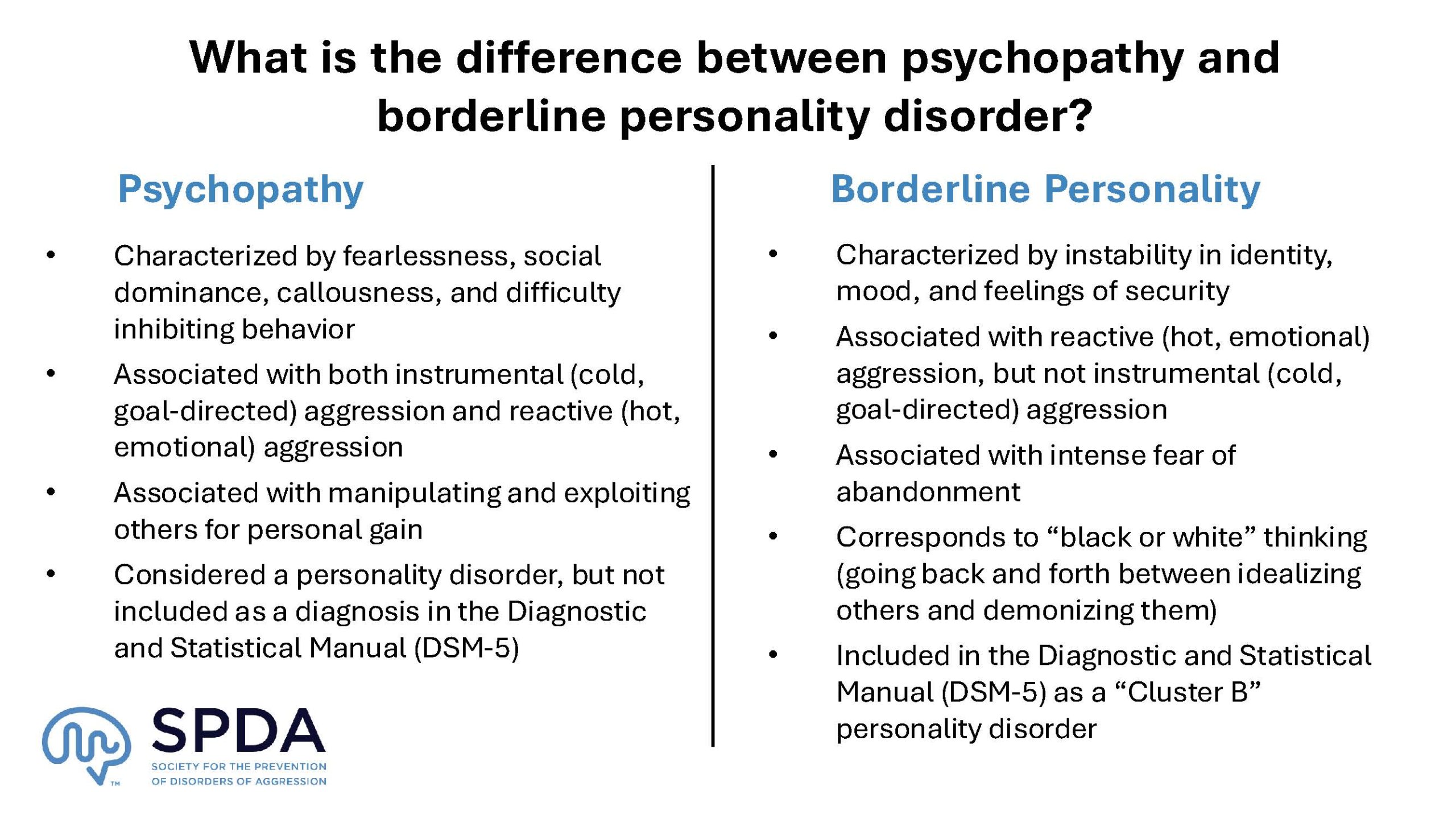

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). BPD is characterized by behaviors that include unstable social relationships and intense displays of emotion, as well as personality traits like impulsiveness and a negative self-image. People with BPD often fear abandonment, may attempt suicide frequently, and report persistent feelings of emptiness. People with this disorder can be aggressive, but aggression is not among the diagnostic criteria. Learn more about distinctions between BPD and psychopathy.

Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD)

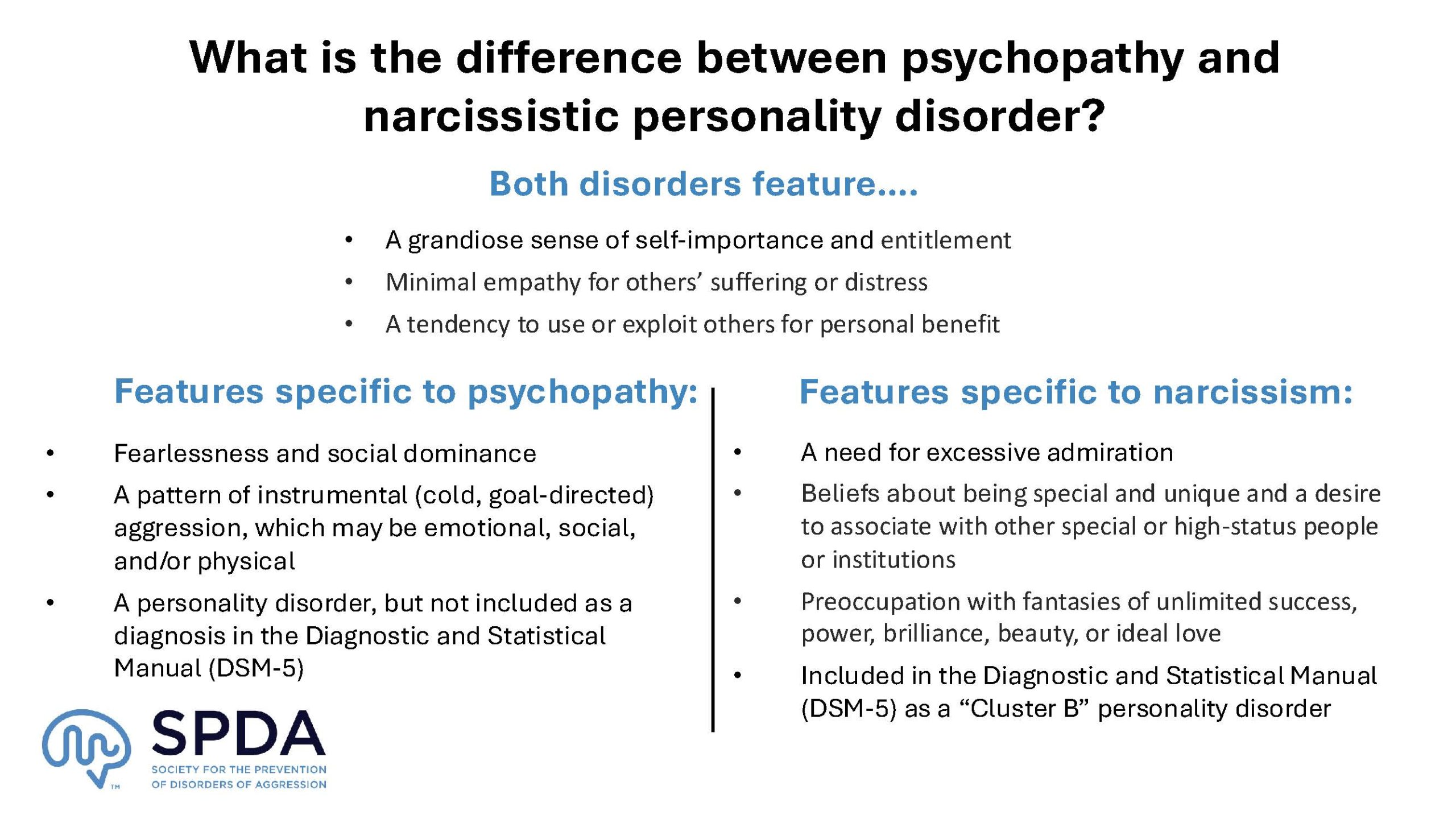

Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD). NPD is characterized by grandiosity, a need for admiration, and lack of empathy. People with psychopathy are typically narcissistic. Thus many people with psychopathy also meet the diagnostic criteria for NPD. However, not all people with NPD are psychopathic. People with this disorder can be aggressive, but aggression is not among the diagnostic criteria. Learn more about distinctions between NPD and psychopathy.

Substance Use Disorders (SUD)

Substance Use Disorders (SUD). SUD are characterized by compulsive use of alcohol and/or drugs despite their harmful consequences. People with addiction (severe substance use disorder) focus on using one or more substances to the point that it takes over their lives. Many people with psychopathy also have substance use disorder(s). Note that substance use can mimic some symptoms of psychopathy. For example, people in withdrawal may lie, steal, or hurt others, including people they love, in an effort to obtain drugs or alcohol. In this case, treatment for substance use alone may improve behavior. People with substance use disorders can sometimes be aggressive, but aggression is not among the diagnostic criteria.

Why don’t we discuss “sociopathy” or “malignant narcissism”?

“Sociopathy” and “malignant narcissism” are terms that you may hear used to describe people who appear to lack empathy, guilt, and remorse and who engage in persistent antisocial behaviors. These terms are sometimes used interchangeably with the term “psychopathy.” However, there are important differences among these terms.

Psychopathy

Psychopathy is the scientific term used to refer to traits that include callousness, antisociality, and disinhibition. There are two forms of psychopathy: Primary and secondary psychopathy. Primary psychopathy is thought to be strongly related to genetic risk factors. People with primary psychopathy generally show stable levels of psychopathy over long periods of time. They have low levels of anxiety and fear, and often do not have histories of severe trauma, abuse, or neglect that can explain their personality and behavior.

Secondary psychopathy is thought to result mostly from environmental factors. People with secondary psychopathy may show more changes in their personality and behavior over time (getting either worse or better). They tend to have high levels of anxiety and fear, and often have histories of severe trauma, abuse, or neglect.

Sociopathy (or Sociopath)

Sociopathy is not a clinical or scientific term. Mental health professionals do not use this term, and it is not a diagnosis. In general, “sociopath” is a term used by the media and the public to describe anyone who engages in violent or antisocial behavior. The term is sometimes used (again, by the media and the public, but generally not by mental health professionals) to refer to people whose antisocial behavior results from trauma or abuse. Thus, its meaning tends to be closer to secondary psychopathy than primary psychopathy.

Malignant Narcissism

“Malignant narcissism” is not a clinical or scientific term, it is not a diagnosis, and there is no scale for assessing it. It is sometimes used to describe people whose extreme narcissism leads them to engage in antisocial behaviors. The traits that are often used to describe malignant narcissism overlap strongly with psychopathy, however, so it may be more scientifically and clinically accurate simply to use the term psychopathy.